It was the moment I knew I was Malaysian.

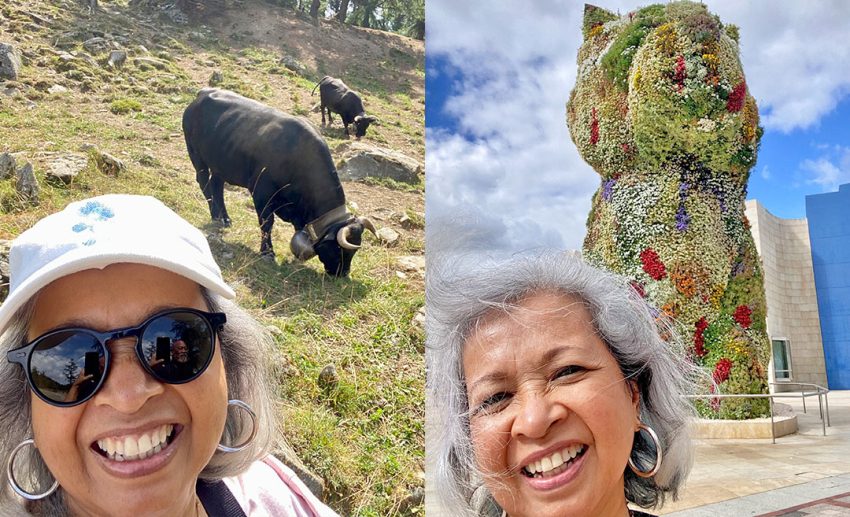

Setting up a dinner date with a friend in Geneva, Switzerland, I asked if he could book us at an Ethiopian restaurant.

“I’ve had enough of bread and cheese,” I said.

After four weeks of travelling in Portugal, Spain, and Switzerland, I was hankering for some flavour. Not that I’m a fussy eater. I love trying different cuisines everywhere I go. Portuguese and Spanish food has benefitted from their past overseas conquests bringing back spices from far-off lands in Asia and Africa. The seafood and meat dishes were amazing, whether traditionally cooked or inventively new.

It’s not that they didn’t have flavour. They just weren’t spicy. “Despite,” as our Lisbon tour guide said, “historically getting rich on the spice trade.”

Ethiopian food served on a large piece of bread and filled with meat and vegetables half-fulfilled my craving. But it still lacked that tongue-tingling sharp taste of chilli, preferably made with belacan. That was when I knew.

It is moments like this that make me aware of where I come from. Back home in our always tumultuous, busy country, with (if you keep up with the news) a multitude of confusing, irritating, and occasionally heartening events, I sometimes forget this part of my identity. When home, I am a female writer and activist, constantly being challenged to maintain those facets of me, as well as a wife and mother. It’s not that I forget what passport I hold, but it retreats to the background when my other identities seem to matter more to others.

As the saying goes, we are all Malaysians only when we go abroad. Partly it is because, among strangers and people very different from us, we reach out to other fellow citizens whenever we come across them. That’s why our students at foreign universities organise themselves into associations and happily celebrate festivals by cooking our signature dishes and wearing our different traditional outfits.

But for someone who prides myself on being very adaptable to wherever I am, there are those moments when I realise that, at core, I am Malaysian. It’s not just about food either. When I was in boarding school in England doing my A-Levels, I remember borrowing a few pence from an English schoolmate to buy a bar of chocolate because I didn’t have my wallet with me at that moment. Her first question, after lending it to me, was, “When are you going to return it to me?”

Although all students are cash-strapped, I found the question shocking and rude. It implied that there was a possibility that I might not return it. Indeed, the Western attitude toward money always puzzled me. I would go out with fellow students for meals and at the end of it, naturally expected to contribute to the cost. But unlike the relaxed Malaysian attitude, I was a bit surprised and embarrassed by the detailed accounting to make sure that everyone paid for exactly what they ate and drank instead of just dividing the total by the number of people. I usually drank less than everyone else, but I really didn’t fuss about paying slightly more than my exact share. No sweating over the small stuff in the interest of friendship, I thought.

It was really these small things that I felt defined me as Malaysian, the moments when I felt culturally different. They usually came as small shocks. I was at a conference in Canada once, and while washing my hands in the washroom, I was astounded by the number of paper towels the Canadian delegates pulled out to dry their hands when I only needed one. Perhaps my hands are smaller, but it occurred to me that the overuse of paper in those countries was probably contributing to climate change, which all of us eventually must suffer.

Not that we really need to travel to have these defining moments. I was once invited to an expat neighbour’s home at 8pm, a time I associate with dinner. Expecting the usual Malaysian abundance of food, or perhaps a proper sit-down meal, I found that the only food being served was little canapés on trays. It highlighted to me the importance of knowing the local culture whenever you live in a different country, not least the type of hospitality that you would find in people’s homes. I eventually left early to have something to eat at my own house.

These incidents may all seem petty, but to me, being Malaysian is not just about waving the flag and singing the national anthem everywhere we go. It is when you are forced to think about parts of you that are quintessentially of your country. In this very globalised world, where almost every high street looks the same, and, as an American friend said, “There’s always MacDonald’s” if you can’t find anything else to eat, it is these little things that only another Malaysian would understand. These seemingly trivial quirks are really what unites us, even if sometimes it seems we spend too much time quarrelling about our differences. How many times do we overhear our distinctive accent somewhere abroad and turn our heads to look for its source? Every tiny bit of familiarity is comforting.

Recently, I was having lunch in a small Japanese restaurant in Geneva. Our server was a handsome young boy, genial and polite, who looked as if he was part-Asian. At the end of the meal, I finally asked him if he was half-Japanese. “Not at all,” he replied, “I’m half-Malaysian.” His mother came from Sibu, Sarawak, and he had lived in Kuala Lumpur for almost half his life. All he wanted now was to get back to Malaysia.

I get you, young man, I get you. There is no place like Malaysia.

Despite all the frustrations and disappointments we often feel when we’re at home, abroad we’re all, even half or wholly, Malaysian.

Happy Malaysia Day, everyone!

*All images courtesy of Marina Mahathir.