Embarking on a journey through Japan goes beyond its stunning landscapes and rich cultural heritage; it also requires a meticulous understanding of local social norms and customs.

In this first instalment of our Japanese Etiquette series, we delve into the intricacies of navigating public spaces in this Northeast Asian country, guided by my experience of living in Japan’s Chiba prefecture since 2016.

From bustling city streets to shared indoor spaces, mastering the art of etiquette is key to experiencing Japan’s charm to the fullest.

1. Asking for help

“Sumimasen” is the most useful Japanese phrase besides “arigatou’” It can mean “excuse me”, “sorry”, and, at times, even “thank you”.

If you need help from a stranger, initiate by saying, “sumimasen.” End conversations with “arigatō gozaimasu”, the polite version of “thank you”. The word arigatō on its own is a casual “thanks” that is used more with family and friends than with strangers.

Translation tools: If you have internet access, type your desired sentence into DeepL, a free and more accurate translation app than Google Translate. If you don’t have internet access, download a Japanese dictionary app before your trip; I’d suggest either Takoboto for Android or Imiwa for Apple users.

Speaking English: Most Japanese people don’t converse in English but recognise beginner phrases like “thank you” and “sorry.” Although English has been taught in school for decades, overall proficiency could be higher.

While there’s lingering racial discrimination in Japan, you’ll generally find that Japanese people are polite and helpful to tourists—unless said tourists behave rudely. All the more reason to learn Japanese manners!

2. Entering indoor spaces

Masks: Face masks are still widely used in Japan, as they were before the Covid-19 pandemic. You don’t have to wear one, but when coughing or sneezing, do use a sleeve or tissue to cover your nose and mouth.

Shoes and slippers: Always remove outdoor shoes at the entrance foyer of a home or hotel room. It’s fine to forgo indoor slippers, but avoid showing holey socks or bare feet. Remove indoor slippers before entering a room with tatami flooring. If you join a gym or exercise class, a clean pair of indoor sports shoes may be required for entry.

Public baths (sentō and onsen): Can you visit an onsen during your period? Yes! Just use a tampon or a menstrual cup. Do you have tattoos? You may need to conceal it—with tape, bandage, or a tattoo cover—before being allowed entry.

Once inside, take a shower before entering the bath area naked. Leave your phone/camera in the changing room locker, but you may bring a small hand towel. Avoid letting your towel or hair touch the bathwater. Don’t chat loudly or swim. Lastly, before leaving, blow-dry your hair (Japanese people do not walk outside with damp hair).

Umbrellas: You’ll probably carry one around in the rainy months of June, September, or October. Before entering a building, shake out droplets and fasten your umbrella. Some malls and supermarkets provide extra-long special plastic bags to keep your umbrella from dripping everywhere.

And, as I’ve reminded my parents several times when they’ve visited Japan: Do not point at things with your umbrella; you might hit someone.

3. Riding trains

Station escalators: If you’re not walking up the escalator, stand on one side (left-hand side in Tokyo, right-hand side in some regions). Place hand luggage and bags on the escalator step in front of you, not beside you.

Waiting for trains: This might seem obvious, but line up on either side of the train doors. Let passengers disembark before you enter.

Don’t do these: Talk loudly, talk on your phone, play a video or song on your phone loudly, occupy more than one seat, and stick out your legs or umbrella while seated.

Hungry? I rarely see Japanese adults eat on the train. It’s permitted, though. In fact, long-distance trains like the shinkansen have tray tables for eating ekiben (bentō meals sold at selected train stations). Just avoid bringing food that has a strong odour or might spill easily. Oh, and while you can eat on trains, it’s rude to eat while walking outside. When Japanese people snack outdoors, they stand still or find a seat.

Priority seats: The noble thing is to give up your seat, especially a priority seat, for the following: elderly, disabled, pregnant, parents carrying young children, and passengers wearing a red medical tag. Unfortunately, I’ve often seen them ignored by fellow Japanese.

When it’s crowded: I was in a tricky situation once – I was pregnant and travelling near Osaka with family and tons of baggage. We were caught off guard by the train seating, which was arranged differently from most trains in Tokyo and had less legroom. An elderly lady got upset that our baggage took up so much space, including one seat (a big no-no).

The lesson? You can’t always prevent it, but large baggage and strollers may make things hard for you and other passengers. If you’re in a big city, try to avoid rush hour (before 9am and between 5pm to 8pm).

Sleeping commuters: What if someone falls asleep on your shoulder? It’s OK to wake them with a tap on their shoulder, shrug them off gently, or choose to be a nice pillow.

4. Physical boundaries

Refrain from touching: Japanese people aren’t touchy compared to many cultures. Hugs and handshakes aren’t the norm; you won’t look cold or distant if you simply bow for greetings and goodbyes.

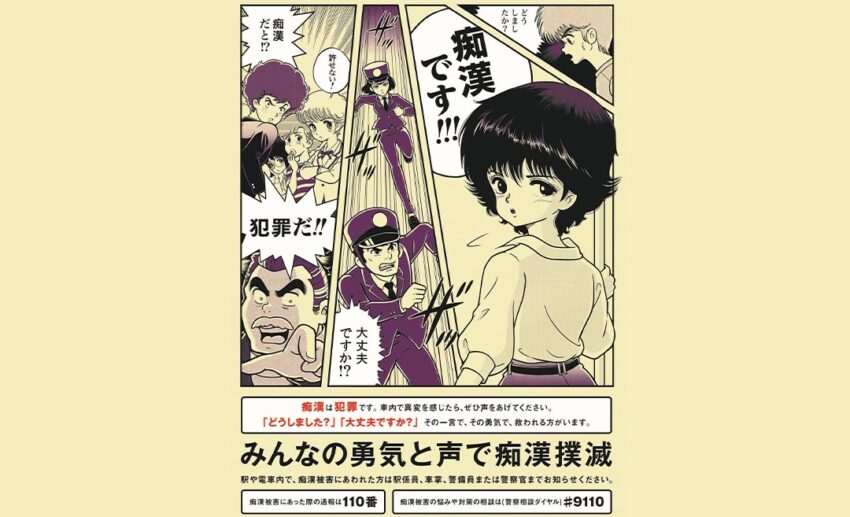

What if someone crosses my boundaries? Japan is comparatively safe. But, like in any country, some women have unpleasant encounters here. Both foreign and Japanese women have experienced groping, stalking, or inappropriate stares. It’s hard not to freeze up when that happens, but here are possible responses:

Confronting a groper or stalker: While Japanese people love quiet and harmony, don’t be afraid to make a scene in this case.

For groping, first, be sure the touch was intentional—not accidental—since this usually happens on a train or bus. Loudly say “chikan!” (groping/groper). You can use the same word to confront a stalker. Or, simply shout anything in your own language. Looking aggressive tends to scare off Japanese stalkers, from what I hear. Alternatively, head for the nearest police booth (there’s often one next to train stations) or convenience store and say that a sutōkā is following you.

Avoid hitting the offender because the first person to engage in physical violence may be found legally at fault.

You can still travel solo! Just practice common sense and trust your intuition. Don’t follow strangers into bars, and watch your drink. Personally, I’ve not experienced any harassment and feel safe walking out to buy a snack at midnight. Japan is still one of the safest countries for solo female travellers.

More tips on travelling in Japan

Have questions? The Reddit forum JapanTravelTips is a good place to ask about not only culture but also advice on itineraries, shopping, etc. There are forums for specific regions too, like TokyoTravel and OsakaTravel.

For more tips on interacting with the locals, read the second part of this etiquette series: ‘Japanese Etiquette, Part 2: Meeting Japanese People‘.

*All images are by the author unless stated otherwise.