For the Chinese of Southeast Asia, Chinese New Year – which marks the end of winter and the start of spring – is the most important cultural event of the calendar.

During this festival, many make their way back to their hometown for a reunion dinner with family on the eve of the first day, a symbol of togetherness and bounty.

This is the most important day of Chinese New Year, which stretches over 15 days, ending with Chap Goh Mei.

For the Hokkiens, however, it isn’t the first but the ninth day that takes pride of place, owing to a calamity that befell the community a long, long time ago.

Who are the Hokkiens?

The Hokkiens are a Han Chinese dialect group originating from China’s southeastern Fujian province.

This coastal province has long had extensive trade links with Southeast Asia, and many of the first Chinese who settled in Southeast Asia from the 14th to 17th century were Hokkien.

These immigrants introduced Chinese practices to the region, resulting in a sizeable corpus of loanwords of Hokkien origin in Malay, Indonesian, and Filipino. Several of these relate to food – mi and pancit (noodles), teh (tea), kicap and toyo (soya sauce) and kuih and kue (cake) are just a few examples.

Many of these Hokkiens, as well as Teochews and Hakkas from neighbouring Guangdong province, ended up marrying local women, giving rise to the hybridised Peranakan Chinese community.

So, what happened?

According to one tale, in the 16th century, pirates who regularly plundered nearby shipping lanes for booty raided a coastal village in Fujian during Chinese New Year, prompting the Hokkiens there to flee.

Other accounts say the Hokkiens were escaping persecution by the ruthless Mongols or even from marauding Cantonese.

Regardless of who perpetrated the attack, the rest of the tale is the same. The Hokkiens fled into a sugarcane field, where they hid and prayed to the Jade Emperor, the supreme ruler of Heaven, for protection.

After searching for several days, the attackers gave up and left, and the Hokkiens cautiously emerged from hiding. By this time, it was the ninth day of Chinese New Year – which was also the Jade Emperor’s birthday.

The Hokkiens saw this as a sign of divine providence. Since then, they have made offerings to the Jade Emperor on the ninth day of the first lunar month to give thanks.

How is it celebrated?

Because of the central role it played in saving the community, sugarcane is an essential part of Hokkien New Year.

A pair of whole sugarcane stalks – symbolising harmony and cooperation – are tied, one on each side, to the offering table or over the main doorway. Joss paper, known as kim chua in Hokkien, is tied to the top of the stalks.

The straight sugarcane also reflects the hope that the Hokkiens will endeavour to be honest, sincere people, while its nodes signify continuous growth.

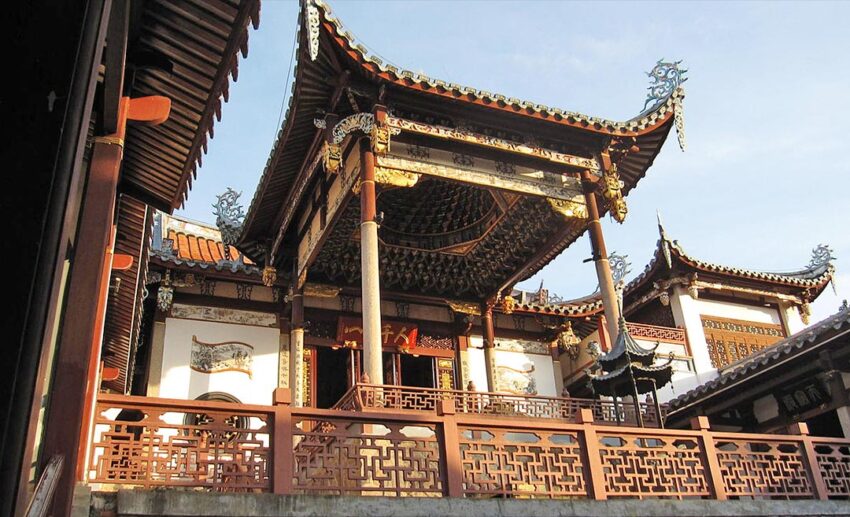

The celebration kicks off with prayers interspersed with chants of “T’i Kong po pi, po pi” (Jade Emperor, protect us) at 11pm on the eighth day, regarded as the start of the ninth day according to Chinese traditional timekeeping.

The offering table, painted red or draped with red cloth, is placed outside facing the sky and weighed down with a full spread of offerings.

These include roast meats, dried cuttlefish, fruits, and sweets such as ang ku kueh (red tortoise cake), t’i kueh (sweet glutinous rice cake), and pink mee ku (steamed buns). A must-have is huat kueh, a rice sponge cake made with fermented rice flour or yeast that’s meant to symbolise the coming year’s fortune – the more it rises, the better.

Once prayers are done after midnight, joss paper is piled up on the ground and set alight, and the two sugarcane stalks are thrown into the resulting fire to burn.

This is followed by the setting off of firecrackers to mark the start of the ninth day and the continued survival of the Hokkien people.

This story was originally published on AirAsia. Zafigo republished this story in full with permission from the publisher, simply because good stories should be read by as many people as possible! If you have stories that will be of interest and useful to women travellers, especially in Asia, please get in touch with us at info@zafigo.com.