It’s not strange for third culture kids to find it difficult to answer the question, “Where are you from?” I often wish I had a straight answer to this; because while my passport might say otherwise, in my heart, the answer is easy — I’m from Malaysia.

At present, it’s been over a decade since my family left Malaysia. I’ve now lived in India for slightly longer than I’d lived in Malaysia but it hasn’t stopped me from feeling ‘Malaysian’.

In spite of all the time away, I still feel Malaysia is my country, my first home and the place that was so formative to my growing up years.

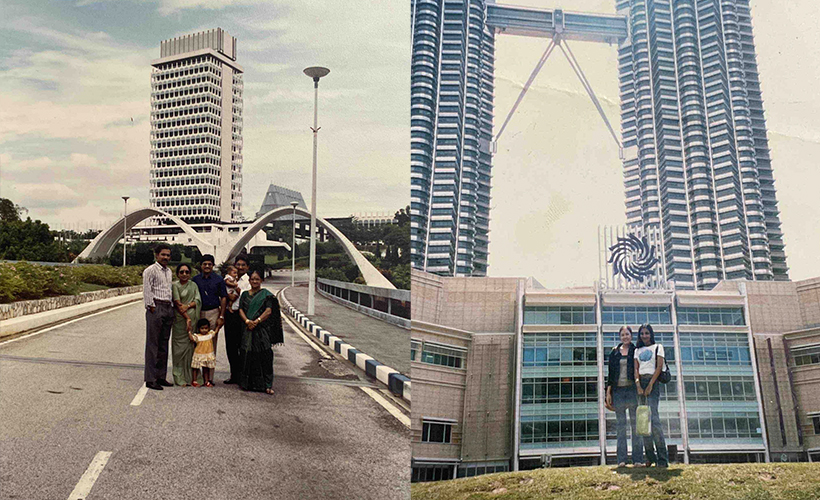

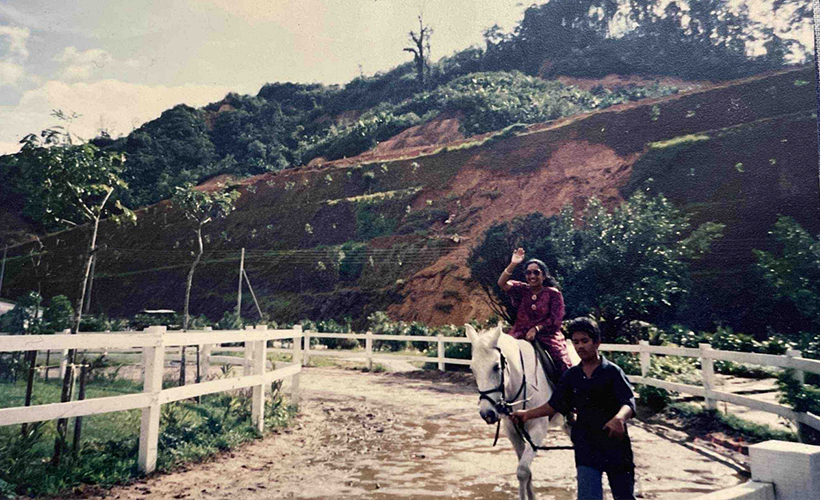

I moved to Malaysia when I was two and lived in Kuala Lumpur (KL) till I was almost 18, with a few years in Penang in-between. My childhood was both quintessentially Malaysian, yet different. I studied in an international school, so Bahasa Malaysia was not a compulsory subject for non-Malaysians, and our school calendar followed the British September-July academic year. This meant we were never at home for the Alam Ria school holiday cartoons (which was a big deal in the pre-Astro, pre-Netflix era), but it also meant that my parents could avoid the school holiday crowds when taking us to Zoo Negara, Genting Highlands, Mines Wonderland, the planetarium, or the butterfly park.

My family moved to Malaysia in 1990, and as a child, I remember the streets decorated with posters of ‘Malaysia Vision 2020’. Although, my idea of 2020 back then was probably something straight out of a Jetson’s cartoon, I was excited. Seeing those posters made me eager to see the promise of the new Malaysia of the 21st century. I was proud to be a part of this history-in-the-making. I was probably less than five years old, but unknowingly, I had already adopted this country as my own.

In primary school, I was a brownie cub. Every week, we would gather after school to learn simple camping tasks (which I still haven’t used ) and recite the brownie promise:

I promise to do my best, to do my duty, to God, my country & the country in which I’m a guest. And to help other people every day, especially those at home and to obey the brownie law.

Although this promise was slightly edited by our girl guide society to be inclusive to a group of international students living outside their home countries, its words held true even after I outgrew the co-curricular activity. Except, I never felt like Malaysia was a country in which I was a guest. It was, still is, and probably always will be the country that most feels like home.

There are many reasons why I will always have a nostalgic love affair with Malaysia, but the strongest one is that Malaysia to me represents childhood. It’s the country that gave me the foundation on which I’ve built the rest of my life on.

If my home country, India, is my parent, she is the strict one — the parent that forced me to grow up. The parent with whom I experienced adulthood. The one who introduced me to the workforce and corporate life. The parent with whom I had to learn how to deal with heartbreak, loss, and death.

Malaysia, on the other hand, is my fun step-parent, with whom I have a fabulous relationship. She is more than a country to me. She represents the uncomplicated nuances of a spoiled childhood. She stands for a time when my grandmother and my father were still alive, my mother was young and beautiful, and my grandfather was independent. A time when the most difficult life decision I had to make was choosing between a packet of Twisties and Super Rings at the grocery store.

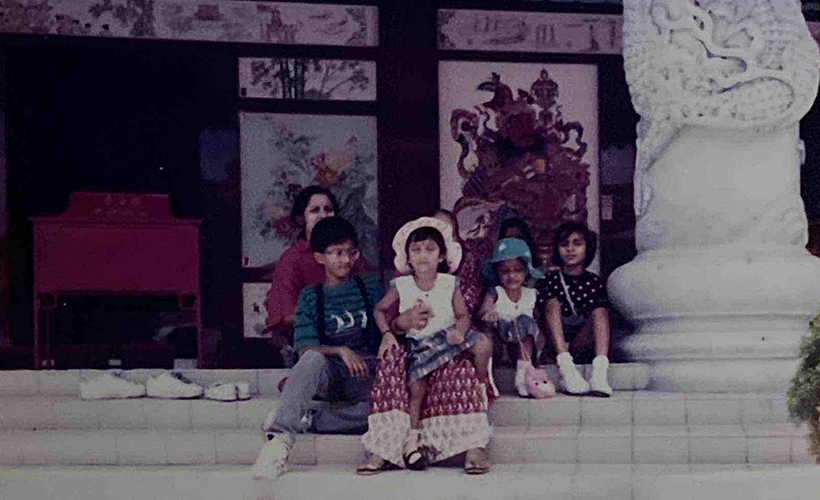

I have so many happy memories of growing up in KL in the ‘90s and early ‘00s. Waking up at an ungodly hour for family picnics to Port Dickson, school trips to the national zoo or museum, the happy ‘bo-beh-bo-beh’ sound of the ‘bread man’ on our street which always meant there was a chance I might get the coveted toy of the week in a box of Tora or Ding Dang. Not to forget, wearing layers in Cameron Highlands for my first taste of cold weather.

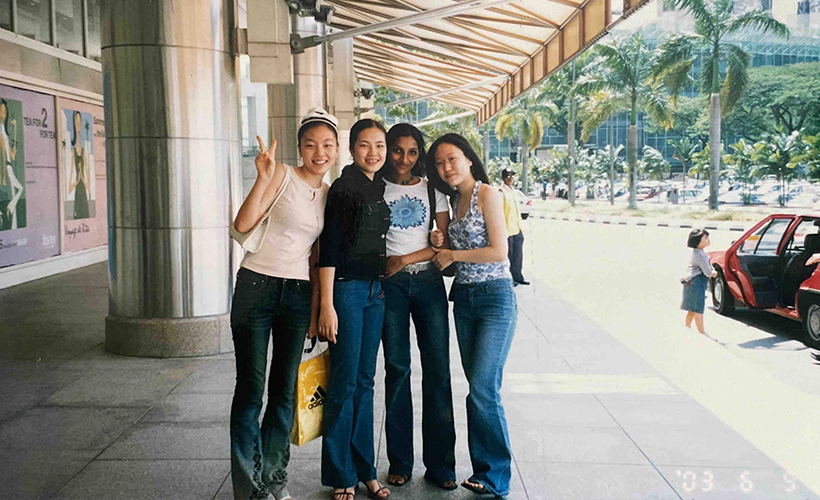

But, just like me, KL grew up. When I entered my teens, family activities were swapped for dates with friends — window shopping expeditions to Ampang Point and KLCC, getting RM5 student haircuts at Great Eastern Mall, dance classes at the Temple Of Fine Arts, and that feeling of being super grown up the first time I sat at a hawker stall table with Tiger Beer on it.

Although Bahas Malaysia wasn’t a compulsory language in school, it was hard not to be drawn to the fun slang of the country that welcomed me as her own. The older I got, the more I found my English being speckled with words like lepak, belanja, and sombong, which, like most foreign languages, don’t have an English equivalent. It’s taken years, but I’ve learnt to drop the occasional lah from my sentences and find a more universal way to communicate the beloved slang words.

When a country adopts you as her own, you adopt her right back. Malaysia welcomed me with open arms and for that, I will always be grateful.

For third culture kids, the word ‘home’ can be hard to define, but I’ve always believed that we are sum of all our experiences. The cities we grew up in, the schools we went to, the foods we ate, and the people who let us into their lives, all build a familiarity that is a semblance of home.

Perhaps that’s why, almost a decade after leaving Malaysia, I still seek out parts of me in travel shows set in Southeast Asia or in a familiar accent on an unfamiliar face. I’m looking for a small fragment of my old home in my new home; and I still haven’t quite figured out where I belong yet.

All I know is, old habits die hard, because I’m always going to be the girl who says ‘yes!’ to rice for breakfast, who sometimes dreams of walking the streets of Bangsar again, and who can still remember all the words to Negaraku.

It doesn’t always matter what your passport says. Home isn’t always the country you were born into, but it’s sometimes the country that raised you. And because of that, no matter where I go, a piece of my heart will always be in Malaysia.