The female, British-accented English caught my attention as I finished dinner.

“What do you suppose is that expression in his eyes?”

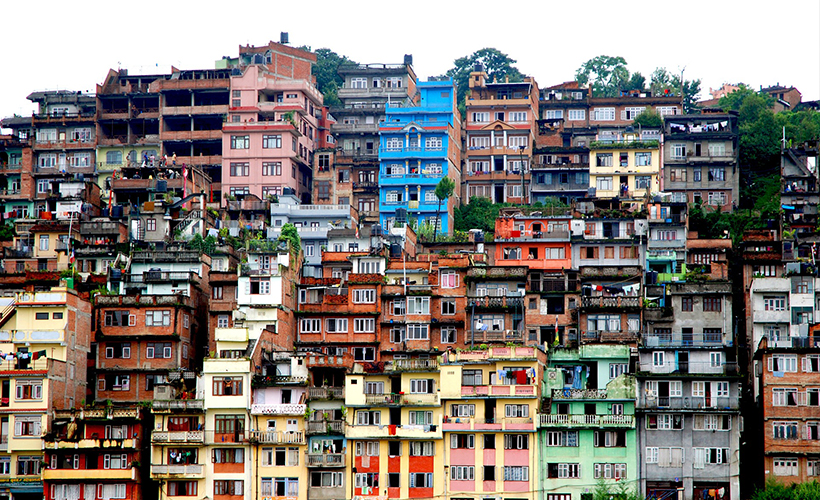

I knew immediately what she meant by “his eyes”. We were dining at the rooftop of a vegetarian restaurant, in the inner ring of buildings surrounding Boudhanath stupa, one of Kathmandu’s UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Like most of the Tibetan-style Buddhist stupas in Nepal, the Boudhanath stupa doesn’t feature a Buddha idol.

Instead, it has a four-sided pinnacle, tapering to a golden pyramidal top. On each side, the same pair of eyes were painted. They’re called ‘Buddha eyes’ or sometimes ‘wisdom eyes’.

The Boudhanath’s wisdom eyes

Indeed, the ones we contemplated on the Boudhanath were a curious pair of eyes. The irises were blue, for one thing. Then, there was the shape. The eye traced a wiggly line, between tear duct and outer edge. It drooped in the middle, rendering a downcast mood. It creased upwards, tilting the eyebrows in a light frown. And the eyelids curved down, suggesting a weariness.

Consequently, I had also wondered for the past few days, what exactly was the expression in his eyes. Considering the complexity of the emotions that were evoked by the shape of the eyes, I’m surprised at how consistently they were drawn. The Englishwoman’s friend replied, after a moment, “Do you think he’s sad? Compassion, maybe?”

Sad? Certainly, I saw reason enough for grief. The mark of the earthquake that struck Nepal in 2015 can still be seen. It destroyed significant parts of the country and damaged several of Nepal’s Heritage Sites. Kathmandu’s Durbar Square is still being restored.

The domain of Lord Shiva

It felt like a kind of irony, when the tour guide there told me that the patron of Nepal was the Hindu deity Shiva, Lord of Destruction. It wasn’t just the earthquake either. Far below, among the throng of people, a group of young Nepalis were collecting donations and soliciting volunteers for the relief of flood victims.

I was there in the Nepali rainy season, during the very same 2017 monsoon flooding disaster that devastated large parts of Nepal, India, and Bangladesh. Millions of people were displaced across the region. The young volunteers brought to mind my Kashmiri host in Pokhara, emptying out his shop’s take for the day to donate to a collection for the stricken people in the south.

In fact, in Pokhara I met two English backpackers who were temporarily marooned in their lodgings in Chitwan by the floodwaters. They told of endangered rhinos being swept away, and related how the hospitable Nepali people put their guests’ safety and comfort first.

Perhaps the Buddha eyes simply reflected its wisdom of how the wheels of the universe turn, andrather than irony, perhaps it is harmony. In such events of destruction, we wonder if we can be called to our better selves – and if we would go.

If the Wisdom Eyes Were Female

“No…” said the first woman reflectively. “He looks a little bit… angry as well. Look at the eyebrows.” Having decided to continue eavesdropping, I looked as well. The sun was preparing to set behind a bank of clouds somewhere to the right of us, but it was still quite light. I had not thought “angry” before, but I guess I could see it. I sipped my tea and thought about the graffiti that caught my notice along one of the main streets of central Kathmandu. They had a theme; perhaps they were painted at the same time. Not recently though, as the paint had faded in parts, and begun to peel, and definitely not by the same artist.

The sombre Kathmandu graffiti art

The graffiti style has one thing in common – all of them are about violence against women. A woman’s silhouette falling away from a pushing hand, an eye bruised shut on a weeping face, a lone tear, falling dark on a cheek, while another dark hand emerged from the nothingness, closing around her throat. It’s one of those things that hadn’t occurred to me before I went, but I’m not surprised by it either. Abuse is still a common distress worldwide.

I’d just returned from trekking in the Annapurnas, where I was guided by a female trekking guide, and assisted by a female porter. They were supplied to me by the first female-owned local trekking company in Nepal, who’d fought to create novel work opportunities for Nepali women so that they’d be empowered with a greater voice in society. I had read up on the norms they hoped to change, and why, and so I chose them precisely for that effort.

What the wisdom eyes have seen

“I suppose so…” said her friend. “I don’t know though. Perhaps concern? Or maybe disappointment?” Close, I thought, but not quite. What was that enigmatic expression, indeed? By this time, I was completely drawn in to their conversation, letting my tea get cold.

I’ve heard it said that democracy in Nepal has not quite gone the way the people hoped. It’s a democracy that followed a civil war, which led to the abolition of Nepal’s monarchy. Disappointingly, Kathmandu didn’t quite evolve a more stable government. A German trekker I met in the Annapurnas told me many Nepalis fled as refugees to Germany during that time. It may also be the reason why all the western bakeries I’ve seen in Nepal are invariably German ones.

The writings on the wall

A different set of graffiti art came to mind then, this time discovered down an alleyway in faraway Pokhara. Generally speaking, if you see political graffiti painted by good artists, coding resistance messages in symbolism, and it’s basically left alone without anyone bothering to paint over them, it’s a sign that things are not quite all right there. I didn’t recognise the faces depicted in the graffiti I saw. I don’t know whether the discontent was local or national. There certainly have been many grievances in Nepal’s modern history to choose from.

That said, you probably wouldn’t notice the political uncertainty in Nepal at all as a visitor. It says something about the culture of the Nepali people – their general character and their resilience – that essential systems and norms of peaceful daily life can still be mediated in spite of it.

The pilgrims beneath the Buddha eyes

Back in the ring around the stupa, the steady flow of Buddhist pilgrims were not thinking of such earthly things.

They circled round and round, walking in reflective meditation, or repeating mantras. The truly devoted came dressed in sackcloth, throwing themselves full length in prostration on the ground, inching forward as they rose back up, oblivious to all else. Pieces of wood strapped on their hands served as a humble layer against the hard ground, raising a rhythmic clack, scrape, clack sound as they slowly progressed – penitent and hopeful, all at once.

I thought of other sacred grounds and other pilgrimage destinations. Likewise filled with souls who have become aware of our better selves – and fully aware that we haven’t lived up to them. Yet rather than despairing, they remain hopeful that we can make amends.

Then all at once I knew the inscrutable expression the believers intended when they painted the wisdom eyes. I guessed the sentiment they were projecting from themselves. The sentiment that impelled so many groups everywhere, to action and activism; inspiring popular support for causes as varied as social rights to environmentalism to veganism.

The eyes of conscience

“Disapproval,” I piped up, catching the eye of the woman who was facing me. She paused in her monologue exploring different shades of disappointment and looked at me. Her friend turned around. “His eyes, it’s disapproval,” I repeated. More specifically, a loving disapproval, like you might see in a parent’s eyes; a look that doesn’t need words.

They both swivelled towards the stupa again, scrutinising. “Disapproval…” one of them repeated softly. “Yes, it is, isn’t it?” We exchanged satisfied, congratulatory smiles.

The desired sentiment was guilt, a hopeful guilt that makes you get back up, make a difference, and strive towards your best self.

Read our last Travel Tale:

The Highs And Lows of Trekking Through Hsipaw, Myanmar

Here’s your chance to get published on Zafigo! We want your most interesting Travel Tales, from memorable adventures to heartwarming encounters, scrumptious local food to surreal experiences, and everything in between.

They can be in any form and length –short stories, top tips, diary entries, even poems and videos. Zafigo is read by women travellers the world over, so your stories will be shared to all corners of the globe.

Email your stories to [email protected] with the subject line ‘Travel Tales’. Include your profile photo and contact details. Published stories will receive a token sum.