In February this year, Malaysia faced a review of its commitments to women’s rights at the 69th session of the Convention for the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) in Geneva. The last time Malaysia submitted its report to the CEDAW Committee was 12 years ago. Countries are supposed to submit them every four years.

The CEDAW Committee is an august body comprising leading experts on women’s rights issues from all over the world. Their task is to review the reports and question the countries concerned on any gaps or slowness in their progress in ensuring women enjoy their full human rights. The issues they want to know about include legislative measures to prevent, alleviate and prosecute violence against women, measures to eradicate child marriage, women’s health issues including reproductive health and rights, and steps the countries are taking to ensure that women make up at least 30 per cent of all decision-making positions, including political positions.

Knowing full well that countries are likely to present very rosy pictures of the state of their women, the CEDAW Committee is also open to receiving ‘shadow reports’ from women’s civil society organisations, which they hope will present a more well-rounded picture of the state of that country’s women. Women’s groups in Malaysia submitted such a shadow report to the Committee so that they could ask the government questions regarding the discrepancies between the official and shadow reports.

It’s timely, therefore, that this year’s theme for International Women’s Day is ‘Press for Progress’.

Suffice to say, the Malaysian government delegation didn’t do very well at all in the face of the Committee’s questioning. When asked about the differing rights situations of Muslim and non-Muslim women in Malaysia, where Muslim women enjoyed less rights when it comes to marriage and inheritance for example, the representative from the Attorney-General’s Chambers syariah (religious law forming a part of the Islamic tradition) division replied by quoting from the Quran, prompting the frustrated Philippine committee member to ask which took precedent, civil or syariah law? Other evasive answers about the age of marriage, violence against LGBT persons, conversion and custody issues, and fatwas against human rights defenders also didn’t impress the Committee. The government delegation seemed wholly unprepared for such knowledgeable questioning.

To her credit however, the head of the government delegation was suitably embarrassed by the poor performance of her team that she invited the civil society team to meet with them afterwards and listened carefully to the many issues they brought up. It wasn’t the intention of the NGOs to embarrass the government, but they had to face the fact that progress towards women’s rights hasn’t only been slow, it’s in fact regressing.

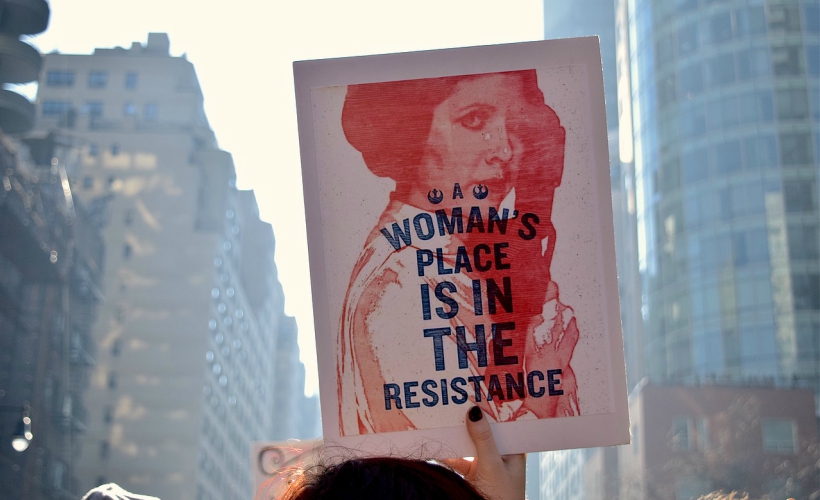

It’s timely, therefore, that this year’s theme for International Women’s Day is ‘Press for Progress’. We cannot assume that as countries develop, women will automatically enjoy their full human rights. Even a country like the United States, which hasn’t ratified CEDAW, is sliding backwards on women. For developing countries like Malaysia, we need to constantly press for progress because complacency breeds not just a plateau in the attainment of our rights, but in some cases, even breeds regression.

Women who are considered too outspoken or critical often find themselves under attack far more viciously than men who say the same things.

For example, the entire country was shocked a few years ago to find out that even though the marriage age for girls was at the already young age of 16, even younger girls, including those aged 10 or 11, can get married with the permission of the syariah court or the Chief Minister’s Office. Even more shockingly, a rapist can try to get away from prosecution by simply marrying his victim.

Violence against women remains a problem everywhere. Every day we read of women and girls being raped – or even killed – for reasons often unknown. In Pakistan, the country was shocked at the brutal rape and murder of 7-year-old Zainab Ansari. In Malaysia, a 17-year-old girl tried to kill herself after having endured a gang rape by nine soldiers, one of whom was her boyfriend. In India, there have been highly-publicised cases of violence against women that have elicited much public outrage.

Women who are considered too outspoken or critical often find themselves under attack far more viciously than men who say the same things.

While in the West the #MeToo and #TimesUp movement is gaining ground, in Asia, it’s yet to take off because of the perennial problem of victim blaming. The few women who’ve spoken up about sexual harassment have found themselves instead being criticised and even blamed for what they endured. A report about how Malaysian female journalists had to endure sexual harassment from politicians they are assigned to interview elicited a typical response from the President of the National Union of Journalists: they should not have dressed too sexily.

The internet too has proven to be an unsafe space for women. Women who are considered too outspoken or critical often find themselves under attack far more viciously than men who say the same things. Very often, the attacks take on personal and sexist tones, sometimes even death threats.

In this type of environment, women’s rights activists have a difficult job ahead of them, especially those who are advocating against the use of religion as a source of public policy and law. But there have been some successes. In India, Muslim women’s groups campaigned for and won a battle to abolish instant divorce in the Muslim community. Jordan abolished Article 308 in their Penal Code which allowed sexual assault perpetrators to escape punishment if they married their victims. Even in Saudi Arabia, there’s been some progress with women now being allowed to drive and some lifting of restrictions on women in the public space.

What this means is that the press for progress in women’s rights must be continuous and consistent, with a lot of perseverance and persistence. None of it will come easily or quickly, especially when decision-makers are mostly men. This is also why it’s important to get women into political leadership positions, in order to make the necessary changes. But this will require women themselves seeing the need to do this. As an example, since Donald Trump became President, more than 26,000 women (a record-breaking number) have decided to enter politics and offer themselves as election candidates.

What will it take for more women to do this? First, it takes knowledge about their situations and rights in order to know what is lacking. Second, it takes some confidence to decide to do something about the situation. This can only be done through the example of role models and the solidarity of the community of women.

We thus hope that we can contribute a little bit to helping women achieve their full human rights by providing the information and support.

This is what Zafigo strives to do. Although our primary focus is on travel for women, we also know that successful travel builds self-confidence. Furthermore, we aim to build a community of women travellers so that they can share their stories, and the lessons they have learned on their travels, and support one another. A community of travellers is a community of people with their eyes and minds wide open, able to see injustice when it happens, either to themselves or others. As Manal Al-Sharif, one of our top speakers at ZafigoX last year said, “Mobility is a human right.” We thus hope that we can contribute a little bit to helping women achieve their full human rights by providing the information and support they need to be mobile and to see the world safely, confidently and successfully.

Happy International Women’s Day! Press on.

Get all the latest travel stories from Zafigo. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

![Overcoming Expectations & Barriers On Women And Telling Their Stories [VIDEO]](https://zafigo.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/IMG_6253.jpg)

![Hitchhiking From Sweden To Malaysia – Of Money, Men And Misconceptions [VIDEO]](https://zafigo.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/IMG_6262.jpg)