In 2016, I visited ‘Hilma af Klimt: Painting the Unseen’ at Serpentine Gallery London. A retrospective of strikingly original paintings from the early 20th century, inspired by spiritualism, hidden worlds in nature, and the occult, af Klimt’s art brought to light the fact this late Swedish female artist was making Abstract art prior to those men, such as Wassily Kadinsky, who we accept as leaders of the Abstract art movement. ‘Hilma af Klimt: Painting the Unseen’ not only reached back to tell her story, but became a vital key in unlocking the breadth of art history to include missing female voices. As a young, female curator/art writer from Malaysia, I was fascinated by this notion of shining a spotlight on women artists in the art world.

In the lead up to Women’s Equality Day, I was invited to reflect on the role of women artists in Malaysia. Looking through Malaysian contemporary art history, I felt pride that Malaysian female artists have long stood at the forefront of the movement. Their art has been exhibited, written about, and collected extensively, showing that there is a genuine sense of equality in Malaysian art.

Lauding the creative dynamism these female artists exhibit, with art that speaks to their own lives as well as our country’s history, notions of ‘being Malaysian’, female identity, and current affairs, points to a forward-thinking social mindset and the need in post-colonial societies for everyone to contribute to new ways of thinking and seeing.

Setting the standards

As new genres opened up in Malaysia’s contemporary art movement, it was often women who set industry-wide standards in making, presenting, and conversing about culture. This trait is traceable back to the early years of a strong contemporary movement, emerging in artists such as Eng Hwee Chu. Born in 1967 in Batu Pahat, Johor, Hwee Chu is oft described as a ‘Malaysian Frida Kahlo’. Much like Kahlo, Hwee Chu’s long and distinguished career is characterised by a series of autobiographical Surreal paintings that cemented the genre’s popularity for local audiences.

In the early 1990s, Hwee Chu’s seminal ‘Black Moon’ series demonstrated new ways of painting by moving past romanticised scenes of daily life, rendered in dreamy tones. Her bold, brooding palettes and busy visuals, which incorporate figures, Chinese symbolism, and objects drawn from her own life, are a look at the quick-stop changes felt as local society tumbled forward in rapid development — all seen through the lens of the Chinese Malaysian experience.

Local audiences sat up and took notice. Hwee Chu won several awards; including the coveted Painting Award at the Salon Malaysia 3 competition (1991). Her strong showing in what is today seen as a key defining event in the emergence of a Malaysian contemporary moment immediately marked her down as a force to be reckoned with, on par with her male colleagues… including her husband, the leading installation artist Tan Chin Kuan.

Understanding the messages

This use of figures and objects familiar to an artist establishes a confessional tone, drawing audiences in. Subtle differences in treatment allow for differing messages to be transmitted, even within the same realm. Contrast, for example, ’Yellow Counter Top’ (2005) by Yau Bee Ling against Hayati Mokhtar’s ‘Penawar’ or ‘Falim House’. Bee Ling’s busy brushstrokes and crowded composition of a domestic scene indicate a fullness seen in her own life, filled with tasks as a mother, daughter, wife, friend, and artist. On the opposite spectrum is Hayati’s notions of dismantling, as she films the packing up of once-full family homes as they are turned into structures devoid of life.

Crucially, both of these women use the very feminine notion of the home as a jumping-off point from which bigger conversations can be had. Bee Ling delves into the recesses of human relationships that build up the world around us, while Hayati immerses her viewer in the disappearance of a recent past. Fascinatingly, she does this both through concept (documenting the last vestiges of lived lives through structures and objects) as well as medium — presenting her videos as larger than life projections in darkened rooms.

The empathy of Hayati’s video installation works extended the boundary of new media art in Malaysia and gained her international recognition. She has exhibited extensively, including at Malmo Sweden, Perth Triennale, and Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Yet, of all the artists in Malaysia that have gained serious international fame, one name consistently stands out — amongst both men and women — that of Shooshie Sulaiman.

Getting tongues wagging

Born in Muar in 1973, Shooshie is of mixed Malay and Chinese heritage. She frequently draws on her own mixed-race experience as a point of instigation for a broader conversation, particularly on the construction of identity in Southeast Asia. It is thus immediately evident that she exhibits the specific talent that Malaysian female artists have to produce art that is consecutively personal and social. Shooshie consistently draws on her own memories, experiences and reactions, and yet, is gifted with the ability to involve the audience within the artworks themselves. Oftentimes, with installations that are site-specific or include intimate contact in some form between viewer and artwork; as seen in ‘Kedai Runcit’ or ‘Kedai Gambar Goldie No 12’.

She has pushed the genre of installation, an important section in Malaysia’s contemporary art movement, to new heights, attracting strong worldwide attention. So accomplished, Shooshie has exhibited at Documenta 12 in 2007, Art Stage Singapore, Singapore Biennale (2011), Asia-Pacific Triennial (2009-10), Continuities: Contemporary Art of Malaysia At The Turn of The 21stCentury, Guangdong Museum of Art, Florence Biennale (2003), and Yokohama Triennale (2017) amongst others.

The innovative streak that repeats amongst Malaysian female artists has not only led to the expansion of existing genres such as installation art, as we see with Shooshie and Hayati, but in the introduction of all-new directions. Such as Umibaizurah Mahir Ismail’s introduction of ceramics into the realm of fine art, particularly as a sculptural medium.

Moving in a different direction — new heights

Umi recounts that she excelled as a student at UiTM, and when the time came to pick specialist majors, it was presumed she would select the competitive route of painting or sculpture. She instead surprised everyone with the choice of ceramics — which was then considered a more industrial pathway. However, just before making this decision, she’d visited an exhibition of Pablo Picasso’s unique ceramic pottery and was blown away by work unlike any she had seen before. She decided to become a master of the medium, delighting in the malleability of clay and the range of colours, textures, and finishes from patinas and glazes, finding ways to create all new forms and shapes from her studio, Pati Satu.

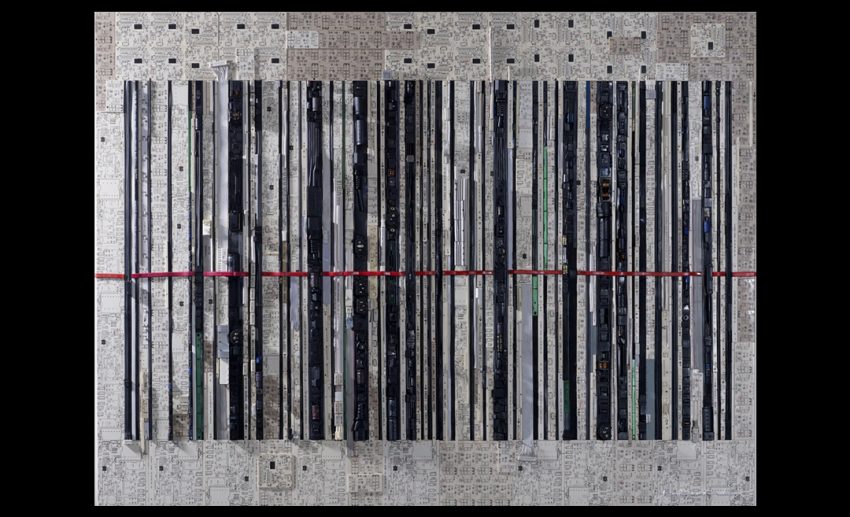

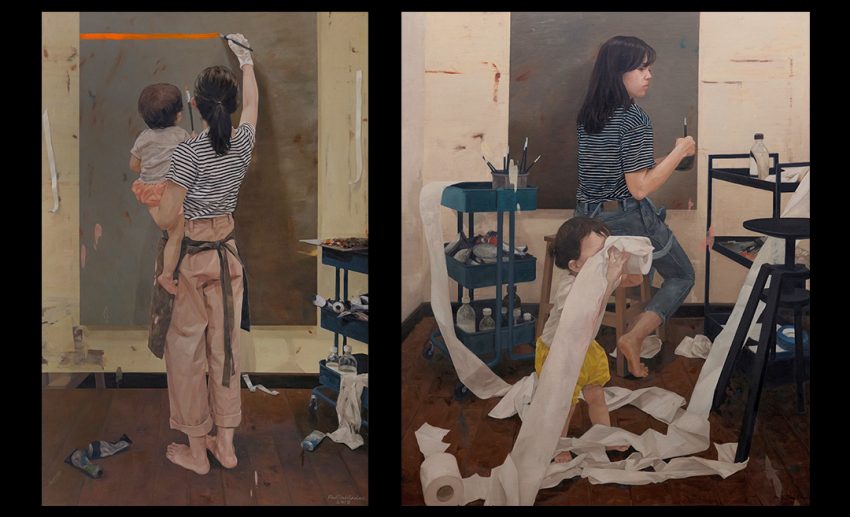

The influence of these women on the local art scene is irrefutable. It has also fostered an environment in which women are able to produce art that speaks to their own experiences. We see this in Fadilah Karim’s self-portraits that feature her daughter at play, or Nor Tijan’s incorporation of technological waste as a medium for sculpture that was inspired by the rise in throw-away consumerism she observed as a mother directed at children. Amongst the current crop, sculptor Anniketyni Madian has built a powerful reputation as the leading artist of a generation.

Anniketyni’s monumental sculptures are layered in both technique and concept as Pua Kumbu patterns from the Iban tribe of her native Sarawak are stylised in discourses on the evolution of local heritage and the part women play in our societies. Her medium of wood has an embedded masculine connotation that she immediately defies by creating a sense of lightness and movement.

More recently, she has been adding resin, another notoriously tricky material, to her sculptures to allow for completely new palettes and glossy finishes. A master of her medium, she is considered Malaysia’s leading sculptor, and regularly represents the country globally. Be it at artist residencies in America, Egypt, and Armenia, producing sculptures for the United Nations in Rome, or presenting her work at major international exhibitions such as the upcoming Perth Triennale 2021.

Recognising these female artists not only allows us to better understand our art history but opens up an insight into the role women play in our community at large. Malaysian women have consistently held positions of power and made economic, legal, and social decisions that have strongly influenced the country’s direction. The arts show us that we are a society that has always, and will continue to rely on, appreciate, and grow from the invaluable contributions of women. These are the characteristics that will propel us forward on the global stage. These are characteristics that embody the spirit of Women’s Equality Day.

To see and learn more about the works of these wonderful Malaysian women artists and the author, follow them on Instagram: Anniketyni Madian, Fadilah Karim, Yau Bee Ling, Nor Tijan, Umibaizurah Mahirismail, and Zena Khan.