Every rock is unique. Very few, however, can match the sheer magnitude of Uluru. Towering 348 meters high, the sandstone monolith is an arresting presence in the heart of Australia’s Red Centre, an Aboriginal homeland where rust-red deserts meet clear blue skies.

Equal parts majestic and magical, the story of this UNESCO World Heritage Site began more than 500 million years ago – long before humans even existed.

It is more ancient than the dinosaurs

The core that formed Uluru was formed more than 500 million years ago during the Cambrian Period. Uluru, together with Kata Tjuta – a cluster of lofty domes located 56 kilometres west – are fragments of the once-mighty Petermann mountain range.

A long, slow period of geological activity that included orogeny, collision, and erosion birthed Uluru into an iron-rich Inselberg or island mountain. As millions of years passed, natural forces like rain and wind gradually stripped away layers of softer sediment, revealing the spectacular monolith we see today.

It is much bigger than it looks

Uluru is so huge that it takes roughly four hours to walk around its base, which spans 9.4 kilometres. Even then, what’s visible above ground is only one-third of its total size. Underground, the Inselberg is buried as far as 2.5 kilometres down.

This natural masterpiece is estimated to weigh a whopping 1.4 billion tonnes, approximately 250 times the total weight of the Great Pyramid of Giza.

It is a natural optical illusion

One of the most amazing things about Uluru is the different ways it can be perceived by the human eye, depending on the time, distance, and angle.

At daybreak, Uluru transforms from dark grey to deep purple, while at sunset, it becomes a coral pink gem that stands out against the changing colours of the sky. In between, in the bright light of the afternoon, the monolith glows a resplendent saffron red hue.

The closer you move towards Uluru, the more features it reveals. What seems like a small, oblong boulder from afar becomes a surprisingly large formation imprinted with a series of dramatic folds, sweeping curves and hidden crevices.

It is deeply sacred to the Anangu people

For the native Anangu people, who have lived in the Red Centre for tens of thousands of years, Uluru is a highly revered site. Uluru plays a part in the creation stories of Tjukurpa, a time-honoured religious philosophy that forms the bedrock of Anangu culture.

Certain outcrops of Uluru, in fact, are believed to represent ancestral spirits. At these sacred spots, the Anangu connect and communicate with the divine realm for guidance and blessings.

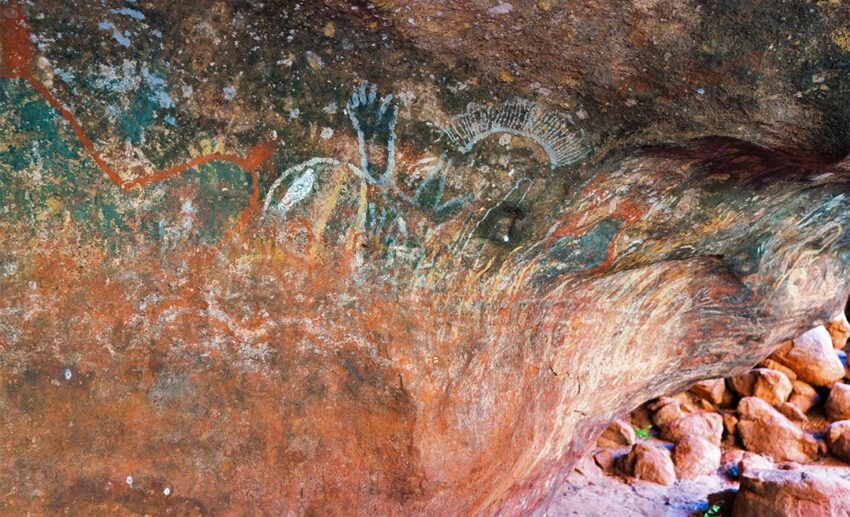

The ancient Anangu, using natural minerals like ash, iron-stained clay, and burnt desert oak, also created ancient rock paintings estimated to be between 10,000 and 12,000 years old.

It conceals a little-known animal kingdom

Living in Uluru’s shadow is an incredible diversity of wildlife, including many species endemic to Australia. These include over 178 bird species, such as honeyeaters and the rare galah cockatoo, soaring above pockets of hardy plants where Goanna lizards and desert dingoes lurk.

Sporting spiny, yellow-brown skin, the thorny devil is a lizard with a gentle disposition that belies its name. When not busy sunbathing, it enjoys eating ants and strolling about in slow, jerky movements with its spiky tail lifted up.

The elusive southern marsupial mole is also known to the Anangu people as itjaritjari. As cute as it is rare, the eyeless, earless mammal has golden, velvety fur, a pink bulbous nose, and spade-like claws, which it uses to burrow in the sand.

It occasionally makes waterfalls

A beautiful scene occurs during heavy downpours when rainfall cascades down various parts of Uluru, creating the illusion of a waterfall. This phenomenon is rare, however, as it hardly ever rains in the Red Centre. It is estimated that only 1 percent of visitors get to witness this one-of-a-kind spectacle.

Although this part of Australia is not synonymous with snowfall, a fortuitous event took place in the winter of 1997 when traces of snow mysteriously fluttered down over Uluru.

It was named Ayers Rock for a while

Uluru was once called Ayers Rock, named after the eighth premier of South Australia, Henry Ayers, by surveyor William Gosse in 1873. The awe-inspiring natural wonder first became an official tourist attraction in 1936, drawing in millions of international visitors, including senior members of the British royal family.

In 1985, after decades of campaigning, the Australian government finally handed back the title deeds for Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park to the Anangu people. It would take another 34 years, however, for a ban on climbing the monolith to take effect.

In 1987, Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park was recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage Site for being an “outstanding living reflection” of age-old indigenous practices that have forged a deep connection between the Anangu and their traditional home.

This story by Irvin Hanni was originally published on AirAsia. Zafigo republished this story in full with permission from the publisher, simply because good stories should be read by as many people as possible! If you have stories that will be of interest and useful to women travellers, especially in Asia, please get in touch with us at [email protected].