“This is Burma, and it is quite unlike any land you know about.”

-Rudyard Kipling

I had doubts prior to confirming my trip to Myanmar, but with a half-decade-old dream of seeing the ancient city of Bagan flirting in my head and recommendations from a dear friend, my partner and I booked our tickets with the World’s Best Low-Cost Airline.

I told Esther (name has been changed), a refugee I worked with, that I was going to visit her country.

“Why would you want to go there?”

“Your country seems beautiful! Why not?” I explained.

“Please don’t go! It is very dangerous!”

I would have explained that it would not be dangerous for me as I was merely a tourist, but that proved too difficult to articulate. All I managed was a “Don’t worry, I will be fine.”

We arrived at Myanmar early on a Saturday morning, groggy from staying up late the night before due to work commitments, before our nine-day trip. After a heartwarming bowl of mokehinka (fish noodle soup) at the Jana Mon Ethnic Cuisine Restaurant, we headed to the Shwedagon Pagoda. We were blown away to say the least. Sure, we read about the golden stupas and had seen numerous photographs of them on Google Images, but nothing, nothing could prepare one for the grandiose of Shwedagon.

After a paid tour of the pagoda — which was worth every Kyat we paid — our guide, who wore thanaka on his face, insisted that we return in the evening. In his words, “You have to come back. It is very nice at night, you won’t regret it!” No truer words have ever been spoken.

Another refugee I had the privilege to work with was 15-year-old Robert (not his real name). When I asked if he would like souvenirs from Myanmar, he replied, “The cream we put on our faces… err… oh, thanaka!”

Thanaka, a yellowish cosmetic paste made from ground bark that serves as sunscreen, is a word so synonymous to Myanmar, as nasi lemak is to Malaysians, and you’d be hard pressed to find a Malaysian who had trouble recalling its name. But here was a child who had been away from his home and culture for so long that he struggled to remember what it’s called.

Next, with much anticipation, we took the night bus to Bagan with JJ Express. Upon boarding the bus, a stranger remarked, “More comfortable than a plane!” Off we went on a 10-hour bus ride to see the much-revered ancient ruins. I must admit, my first impression of Bagan from inside a taxi was nothing to boast about. The ruins seemed rather sparse.

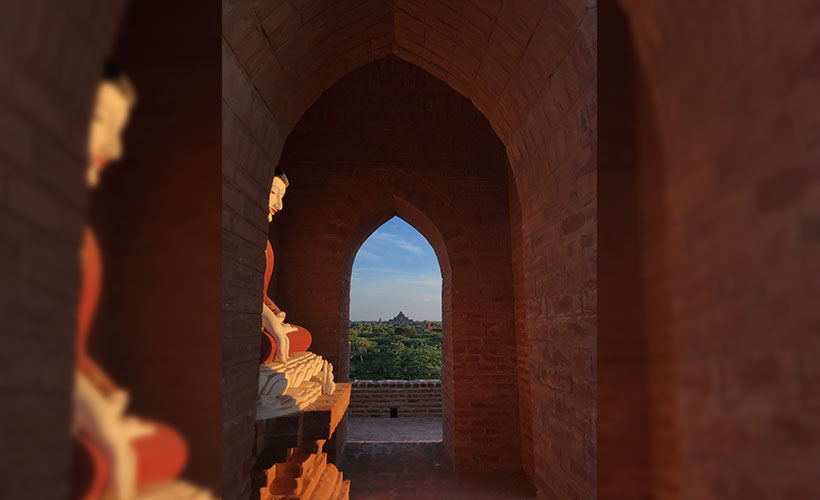

However, the moment we hopped on the popular e-bike, Bagan became a whole new world! Stupas and temples gold, brown, and white sprouted like wild mushrooms through the plains. With the experience of exploring temple after temple, both stupendous and small; the thrill of journeying through dust road in the hot sun (I say road, but really, it was mostly dust); and the numerous stops for milkshakes at Date Cafe, Bagan grew on me. We spent mornings chasing sunrises and evenings waiting for it to set, all in serenity.

Just when I thought I had fallen in love with the archaeological park, that I’d experienced the best it had to offer, and that I could not possibly love it anymore than I already did, I tried the tamarind leaf salad! At this juncture, I must mention that I was never a salad person. If I had a salad — and that has happened maybe twice in 30 years — said salad had to be served with chicken or salmon and drenched in copious amounts of sinful sauces. The tamarind leaf salad, however, was delightful from the first bite. It took no convincing at all for me to finish my vegetables!

Before leaving Bagan, we decided to hire a tuk-tuk (an auto rickshaw) for a trip to Mount Popa. As we drew closer to Mount Popa, villagers started appearing, running after our tuk-tuk. Being the ignorant tourists that we were, we merely thought they enjoyed a good sprint, albeit in scorching temperature. As we went further, or rather, nearer to Mount Popa, more people waited on both sides of the winding road; young and old, men and women, and a few mothers with babies in their arms. The younger ones ran after each passing vehicle while the older folks appeared to be seeking alms. Then, we watched in dismay as passengers from other vehicles literally threw money out the windows. The villagers manoeuvred among moving cars and tuk-tuks to pick notes off the road!

No trip would be complete without a visit to the museum. On our last day in Bagan, we decided to pop by the Bagan Archaeological Museum 60 minutes before closing time. Our only wish was that we skipped our ice-cream session and started much earlier instead.

Having returned to Yangon, there were two highlights of our trip. First, the National Museum, followed by the Rangoon Tea House. We allocated three hours for the National Museum and this too was far too ambitious. With five storeys of astonishing artefacts and breathtaking art, one would need at least half a day to fully take in what the place had to offer. A typical Malaysian, I ordered the famed biryani at the Rangoon Tea House and a warm cup of Burmese milk tea. The biryani was wonderful and be warned, the 15-variety Burmese milk tea will have you hooked from the first sip. Whether you prefer your tea bitter, sweet, rich or not, there is something for everyone at the Rangoon Tea House.

Upon my return home and to work, I went to Esther and told her that I loved her home — that it was the most beautiful place I had ever visited, that food was beyond amazing, and her people were absolutely lovely!

“Did you see very rich people?” She waited quietly for an answer.

“Yes, I did.”

“Did you see very poor people?” I couldn’t lie.

“Yes, I did. Don’t worry, we will do something about it one day.” Just like that, I made a promise.

Esther grew up in the district of Falam in north-west Myanmar. She is Chin and has just turned 13 in May 2019. Her father went to the United States early this year, in search of a better life. Her family is to join him there when he is settled. The young woman enjoys a good bowl of soup noodles and spends her evening after school helping her mother at home — cooking, cleaning, and caring for little children. Approximately five years ago, Esther and her family journeyed to Malaysia by boat. When asked how long the journey took, she simply said, “I don’t know, maybe a few days. I was afraid. I just slept. Many strangers.”

Esther wants to be a missionary doctor when she grows up.

“So that I could make my country and my family proud, and I can help poor people like me,” she added.

Esther has never been to Bagan.

Through many of our travels, we learnt to appreciate what we take for granted — from witnessing barefoot children sell crafts and maps at the Angkor Archaeological Park, to teenagers shoving menus in our faces outside restaurants in the bustling streets of Yogyakarta, to having our feet massaged by vibrant youth in Ho Chi Minh city — we learnt that we are ‘lucky’ to have had the opportunity to go to school; to read and write in buildings equipped with all things we consider basic necessities (proper sanitation, for example). Many children in places like Kampung Tapai and Long Lamam in Malaysia only recently got schools to attend with the help of local NGOs. Some children though, do not even have a right to formal education.

Travelling is in itself a privilege, a privilege that reminds us of how privileged we are. Apart from learning to appreciate our privileges, can we not take little steps to help others? Perhaps we can, perhaps, we will.

These young people are resilient, they are strong. They are kind. They work very hard. They do not think twice about striving towards a better future to help others. They are refugees.

*All photos courtesy of the author unless stated otherwise.