It’s never easy losing a parent. It doesn’t matter if their death was sudden or if it was the culmination of a long illness, there is never an easy way to accept it.

Losing a parent to COVID-19 though, is probably one of the hardest ways to lose them. On 24 May, 2021, my father lost a 17-day battle to COVID-19 and passed away from post-COVID complications. Prior to catching a very mild case of the virus, my father was perfectly healthy. Exactly one week before he was hospitalised, as rumours of a deadlier second wave of COVID-19 in India circulated, he and I switched off the news, made popcorn, and had an Avengers marathon at home with my sister.

The funny thing about tragedy is, until it happens to you, it’s easy to believe it never will.

In early 2020, when India went through her first COVID-19 wave, we stocked up on sanitiser and stayed home. We watched the

news, saw the horrors of stranded migrant workers and the death toll rising, but even at its peak, the virus still felt very far away.

I still remember a conversation I had with a colleague towards the fag end of February 2020. He was debating cancelling his planned vacation to the coastal town of Goa due to the COVID-19 scare that was slowly mounting across the world. I couldn’t bring myself to share his fears and encouraged him to go. In spite of the ominous tone the news had started taking, I was confident. India was a country of over one billion people, many of whom were daily wage labourers. There was absolutely no way a country that size could ever shut down. We didn’t have the luxuries of first world countries, we couldn’t have a lockdown.

In the weeks that followed, this blind positivity was what kept me (and several thousands of other Indians) going. We already lived in pollution, surely our immune systems would be able to beat a ‘flu’. Besides, we had been putting turmeric in our food long before the term ‘golden milk’ was even coined. That had to give us super-immunity, right?

On 22 March, 2020, India officially went into a lockdown. In the weeks that followed, middle- and upper-class India continued to survive, banging utensils from our balconies and lighting candles. We sympathised with stranded migrant workers as we sipped our Dalgona coffee and took pictures of our work-from-home (WFH) desks for the ‘gram. Despite life starting to resemble a never-ending Black Mirror episode, it continued to go on. COVID-19 was a battle that we spoke about, but one that we were yet to be drafted for.

As the year went on, we spoke less and less about COVID-19. We let our guard down, casually meeting friends, removing our masks to beat the heat, forgetting our sanitisers and letting go of all pretence of social distancing. Some of us took advantage of the new WFH lifestyle, leaving big cities to move to the mountains or to the seaside. The social media accounts of India’s privileged showed off pictures of exotic holidays in the Maldives and slightly less exotic parties in Goa. Politicians held election rallies and citizens flocked to places of worship.

We were unprepared, but more importantly, we were careless.

In mid-April 2021, the second wave of COVID-19 hit India like a tsunami. We shouldn’t have been surprised, but we were. In the panicked weeks that followed, India trended on social media for all the wrong reasons. The country’s Internet-savvy generation became her warriors with the hashtag #HelpIndiaBreathe trending globally on Twitter.

For a country that produces one of the highest number of doctors in the world, our medical infrastructure was at its weakest. We didn’t have enough beds, oxygen, or even doctors to handle the increasing number of COVID-19 cases. Indians all over the country came together to pool resources for oxygen, blood plasma, and hospital beds. Indians were dying, not from the virus, but from lack of immediate medical attention.

My father, along with four family members tested positive for COVID-19 in the first week of May. Three days after his positive result, his oxygen saturation began to drop. It took us 12 hours to find him a hospital bed and another 24 hours to find him an ICU bed. My father spent the last 17 days of his life in an ICU with 60 patients and just two doctors working round-the-clock to save them.

The 17 days my father spent in the ICU were the hardest two weeks of my life. I tethered precariously between hope and despair, not knowing what was happening and not being able to see or speak with my father. My family and I lived 17 years in those 17 days, yet we are considered lucky.

We’re lucky because we managed to find my father not just a bed but an ICU oxygen bed at a leading private hospital. We’re lucky because we had the financial means to buy him potentially life-saving injections and steroids at three times their original price from the black market. We’re lucky because after he passed away, the hospital gave us his body rather than conduct a mass burial that has been the fate of several COVID-19 deaths. Most importantly, we’re lucky because we were able to have a small funeral to allow us to complete the appropriate Hindu rituals believed to help a departed one’s soul attain peace.

There are so many families who weren’t so lucky, and for them India is grieving. The emotional and mental consequences of COVID-19 far outweigh the economical consequences of the virus. One of the most difficult things I am trying to come to terms with is not knowing what the last 17 days of my father’s life were like. Accepting the knowledge that someone so loved died alone is something that continues to break my heart every single day.

COVID-19 robs from mourning families the ability to grieve as a community. To remember and celebrate the life of the dead together and the ability to aid each other to a sense of normalcy. In traditional Hindu culture, the mourning period usually sees friends and relatives providing emotional support and sustenance to the bereaved family through food and prayer.

After my father’s funeral, my mother and my sisters came home to an empty house and kitchen. In these pandemic times, we had no choice but to take care of each other through our grief and mourn solo. The frustration of not having family or friends near us made a challenging period so much more difficult. Yet, we’re lucky, because the three other members of our family recovered from the virus.

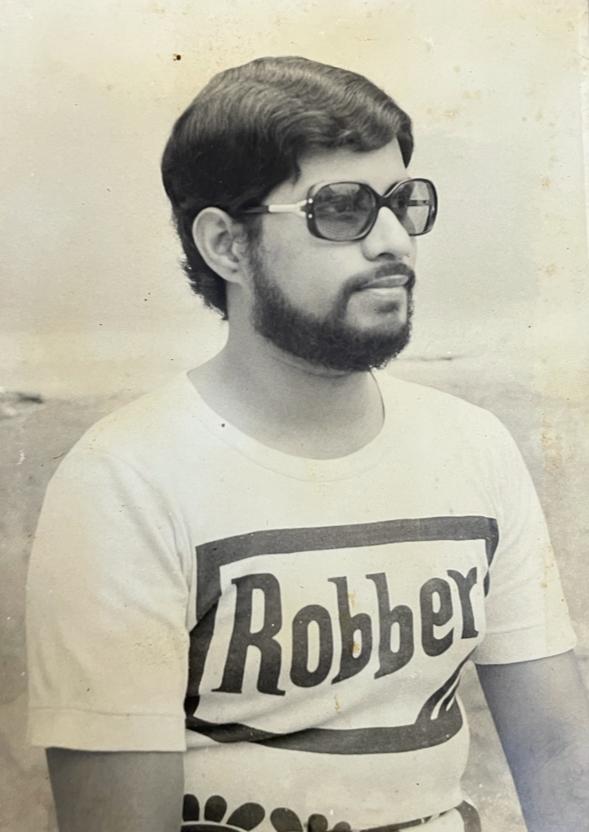

The idea of lucky may have gained a new meaning in the COVID-era, but my father’s death is not just a statistic. Behind the number, he was also a beloved husband, father, father-in-law, brother, uncle, doctor, and a friend. He was a man who was kind and gentle, who taught me the meaning of true love, and who gave his family and community the best he could.

My father didn’t have to die but he did. I can’t change what happened, but I can strive to not let his death (or the deaths of millions of others across the globe) be in vain. As COVID-19 cases start to decrease and the vaccine becomes more available, it can be tempting to think of going back to a ‘normal’ world. As we try to collectively glue back the parts of our broken lives, let’s not recklessly jump back to normalcy. Double-mask, sanitise, and continue to avoid crowds.

The world is broken and we’re still working to fix it. It’s now more important than ever to be gentle and considerate with each other. To one person, it may be a quick unmasked outing, but to someone else, it could cost a life. My father didn’t have to die. Don’t be the reason someone else does.